A general comment on this blog's [The Slack Wire] content

Blog-Reference

It is widely known that the representative economist does not understand how the economy works. Many explanations have been advanced. Putting aside all individual specifics and exceptions for the moment, the main reason is this.

Neither Classicals, nor Walrasians, nor Marshallians, nor Marxians, nor Keynesians, nor Institutionalists, nor Monetary Economists, nor Austrians, nor Sraffaians, nor Evolutionists, nor Game theorists, nor Econophysicists, nor RBCers, nor New Keynesians, nor New Classicals ever came to grips with profit (cf. Desai, 2008). Hence, 'they fail to capture the essence of a capitalist market economy' (Obrinsky, 1981, p. 495).

Neither orthodox nor heterodox economists understand the two most important phenomena in the economic universe: profit and income (2014b; 2014a). Because of this economists have nothing to offer in the way of scientifically founded advice.

“In order to tell the politicians and practitioners something about causes and best means, the economist needs the true theory or else he has not much more to offer than educated common sense or his personal opinion.” (Stigum, 1991, p. 30)

It is important to distinguish between political and theoretical economics. In political economics 'anything goes'; in theoretical economics, scientific standards are observed. The fundamental rule that guarantees the self-government of the scientific community demands to accept refutation. Refutation refers to material and formal consistency.

“In economics we should strive to proceed, wherever we can, exactly according to the standards of the other, more advanced, sciences, where it is not possible, once an issue has been decided, to continue to write about it as if nothing had happened.” (Morgenstern, 1941, p. 369)

Political economics is ignorant of this rule and preoccupied with recycling 'dead ideas' (Quiggin, 2010). This explains the secular stagnation of economics.

Because they lack the correct profit theory the contributions to this blog cannot claim to offer more than personal opinion. Of opinions, though, economics always had plenty. What is needed is knowledge ― scientific knowledge, that is.

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Desai, M. (2008). Profit and Profit Theory. In S. N. Durlauf, and L. E. Blume (Eds.), The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics Online, 1–11. Palgrave Macmillan, 2nd edition. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2014a). Economics for Economists. SSRN Working Paper Series, 2517242: 1–29. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2014b). The Three Fatal Mistakes of Yesterday Economics: Profit, I=S, Employment. SSRN Working Paper Series, 2489792: 1–13. URL

Morgenstern, O. (1941). Professor Hicks on Value and Capital. Journal of Political Economy, 49(3): 361–393. URL

Obrinsky, M. (1981). The Profit Prophets. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 3(4): 491–502. URL

Quiggin, J. (2010). Zombie Economics. How Dead Ideas Still Walk Among Us. Princeton, Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Stigum, B. P. (1991). Toward a Formal Science of Economics: The Axiomatic Method in Economics and Econometrics. Cambridge: MIT Press.

This blog connects to the AXEC Project which applies a superior method of economic analysis. The following comments have been posted on selected blogs as catalysts for the ongoing Paradigm Shift. The comments are brought together here for information. The full debates are directly accessible via the Blog-References. Scrap the lot and start again―that is what a Paradigm Shift is all about. Time to make economics a science.

December 31, 2014

Deflation, saving, and employment

Comment on Asad Zaman on 'Why does aggregate demand collapse?'

Blog-Reference

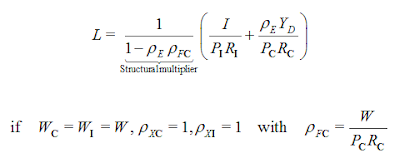

Of course, you are right that deflation may become a problem. The crucial point is that the popular idea of the functioning of the price mechanism is mistaken. What is needed first is the correct price theory (2014) which delivers the correct Employment Law (2014b, p. 9, eq. (22)). Roughly speaking, if the product price (for the economy as a whole) falls faster than the wage rate the employment effect is positive under the condition that all other parameters remain unchanged. If the wage rate falls faster the employment effect is negative. On closer inspection, it turns out that there are two types of deflation. As you rightly pointed out, there are also secondary effects on the real value of debt but this is a separate issue. Resume: neoclassical economics got the price mechanism wrong.

Of course, Wolfgang Waldner is also right. If the relation between saving and income increases the employment effect is negative.

All these effects are captured by the Employment Law, see Wikimedia AXEC07 and (2014b, p. 9, eq. (22)).

Blog-Reference

Of course, Wolfgang Waldner is also right. If the relation between saving and income increases the employment effect is negative.

All these effects are captured by the Employment Law, see Wikimedia AXEC07 and (2014b, p. 9, eq. (22)).

Scientific thinking: Aristotle is right, Leijonhufvud is wrong

Comment on Lars Syll on 'Mainstream macroeconomics distorts our understanding of economic reality'

Blog-Reference

Each paradigm stands or falls with its premises: “When the premises are certain, true, and primary, and the conclusion formally follows from them, this is demonstration, and produces scientific knowledge of a thing.” (Aristotle, Analytica)

The axiomatic foundations of Orthodoxy are wrong and this fully explains its failure. From this does not follow that axiomatization is wrong. This is Leijonhufvud's error.

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

Blog-Reference

The axiomatic foundations of Orthodoxy are wrong and this fully explains its failure. From this does not follow that axiomatization is wrong. This is Leijonhufvud's error.

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

For details of the big picture see cross-references Axiomatization.

***

Wikimedia AXEC121i

No choice

Comment on 'Mainstream macroeconomics distorts our understanding of economic reality'

There is almost universal consent that orthodox economics is a failure. This leaves anyone with the option to ignore or to replace it. To filibuster about it is not a real option.

It is pretty obvious that the failure of theoretical economics is neither the only nor the worst problem of humankind. Under the broader perspective, the problem whether the earth is blown up by human wickedness/stupidity, a natural cataclysm, or by an unknown extraterrestrial entity is the ultimate problem.

However, being economists, we have to admit that -- at the moment at least -- we cannot solve the existential problem of humanity. As a matter of fact, we have not yet answered the question of how the economy works. And this, certainly, was not due to a lack of good will. Science is a trial and error process and so far the trials were not successful.

Since Orthodoxy is a failure and Heterodoxy has not yet come up with a better paradigm the actual option is either to establish a more balanced pluralism of false theories or to promote the required paradigm shift.

By definition, the one and only thing economists owe the world and humankind is the true economic theory.

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

There is almost universal consent that orthodox economics is a failure. This leaves anyone with the option to ignore or to replace it. To filibuster about it is not a real option.

It is pretty obvious that the failure of theoretical economics is neither the only nor the worst problem of humankind. Under the broader perspective, the problem whether the earth is blown up by human wickedness/stupidity, a natural cataclysm, or by an unknown extraterrestrial entity is the ultimate problem.

However, being economists, we have to admit that -- at the moment at least -- we cannot solve the existential problem of humanity. As a matter of fact, we have not yet answered the question of how the economy works. And this, certainly, was not due to a lack of good will. Science is a trial and error process and so far the trials were not successful.

Since Orthodoxy is a failure and Heterodoxy has not yet come up with a better paradigm the actual option is either to establish a more balanced pluralism of false theories or to promote the required paradigm shift.

By definition, the one and only thing economists owe the world and humankind is the true economic theory.

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

The universal Profit Law and the multitude of unique historical circumstances

Comment on Lars Syll on 'Piketty and the elasticity of substitution'

Blog-Reference

The crucial point is to distinguish between total profit for the (world) economy as a whole and the distribution of profit among firms. The theoretical point to start with is conventional profit theory which asserts that total profit is zero: “The consensus to date has been that it is mathematically impossible for capitalists in the aggregate to make profits.” (Keen, 2010, p. 2)

This assertion is fully accepted by methodologists: “But, from the macro perspective of Walrasian general equilibrium, the total profits in this case cannot be other than zero (otherwise, we would need a Santa Claus to provide the aggregated positive profit) but this does not preclude the possibility of short-run profits and losses of individual firms canceling each other out.” (Boland, 2003, p. 150)

The curious thing is that aggregate profit has been greater than zero for most of the time in most of the known market economies up to the present. This is an empirical fact. Hence there is something wrong with the conventional profit theory (Desai, 2008, p. 10). And, clearly, when the profit theory is wrong then the distribution theory is wrong too (2014a). This is the main argument against Piketty.

Now for the constructive part.

First of all, it is necessary to show how positive overall profit comes into existence and how it can be maintained over any stretch of time. The structural axiomatic paradigm achieves this in a formally rigorous way (2013; 2011). For the elementary production-consumption economy, the testable macroeconomic Profit Law is given on Wikimedia AXEC29

Now, the second point is the distribution of total profit Qm among the firms that constitute the economy. Here additional factors come into play. For example firm A increases productivity, firm B slashes wages, firm C gets a big contract to build weapons, etc. All these historical events effect a redistribution of total profit which is given by the Profit Law. It is quite clear that there is no such thing as a historical law: “That is why Descartes said that history was not a science — because there were no general laws which could be applied to history.” (Berlin, 2002, p. 76)

How Ricardo or Bailey made their individual profits is a historically unique story that unfolds within the framework of structural laws. How universal economic laws and unique historical events play together has been shown in (2014b).

All feathers are subject to the Law of Gravitation, but the trajectory of a flying feather is a unique historical event. Scientists are not primarily interested in the latter but in the underlying law. Likewise in economics, there is the Profit Law (= scientist's real reality) and the history of the distribution of overall profit among individual firms (= laymen's commonsensical reality).

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Berlin, I. (2002). Freedom and Its Betrayal. London: Chatto Windus.

Boland, L. A. (2003). The Foundations of Economic Method. A Popperian Perspective. London, New York: Routledge, 2nd edition.

Desai, M. (2008). Profit and Profit Theory. In S. N. Durlauf, and L. E. Blume (Eds.), The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics Online, 1–11. Palgrave Macmillan, 2nd edition. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2011). The Emergence of Profit and Interest in the Monetary Circuit. SSRN Working Paper Series, 1973952: 1–23. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2013). Debunking Squared. SSRN Working Paper Series, 2357902: 1–5. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2014a). The Profit Theory is False Since Adam Smith. What About the True Distribution Theory? SSRN Working Paper Series, 2511741: 1–23. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2014b). The Synthesis of Economic Law, Evolution, and History. SSRN Working Paper Series, 2500696: 1–22. URL

Keen, S. (2010). Solving the Paradox of Monetary Profits. Economics E-Journal, 4(2010-31). URL

Blog-Reference

The crucial point is to distinguish between total profit for the (world) economy as a whole and the distribution of profit among firms. The theoretical point to start with is conventional profit theory which asserts that total profit is zero: “The consensus to date has been that it is mathematically impossible for capitalists in the aggregate to make profits.” (Keen, 2010, p. 2)

This assertion is fully accepted by methodologists: “But, from the macro perspective of Walrasian general equilibrium, the total profits in this case cannot be other than zero (otherwise, we would need a Santa Claus to provide the aggregated positive profit) but this does not preclude the possibility of short-run profits and losses of individual firms canceling each other out.” (Boland, 2003, p. 150)

The curious thing is that aggregate profit has been greater than zero for most of the time in most of the known market economies up to the present. This is an empirical fact. Hence there is something wrong with the conventional profit theory (Desai, 2008, p. 10). And, clearly, when the profit theory is wrong then the distribution theory is wrong too (2014a). This is the main argument against Piketty.

Now for the constructive part.

First of all, it is necessary to show how positive overall profit comes into existence and how it can be maintained over any stretch of time. The structural axiomatic paradigm achieves this in a formally rigorous way (2013; 2011). For the elementary production-consumption economy, the testable macroeconomic Profit Law is given on Wikimedia AXEC29

How Ricardo or Bailey made their individual profits is a historically unique story that unfolds within the framework of structural laws. How universal economic laws and unique historical events play together has been shown in (2014b).

All feathers are subject to the Law of Gravitation, but the trajectory of a flying feather is a unique historical event. Scientists are not primarily interested in the latter but in the underlying law. Likewise in economics, there is the Profit Law (= scientist's real reality) and the history of the distribution of overall profit among individual firms (= laymen's commonsensical reality).

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Berlin, I. (2002). Freedom and Its Betrayal. London: Chatto Windus.

Boland, L. A. (2003). The Foundations of Economic Method. A Popperian Perspective. London, New York: Routledge, 2nd edition.

Desai, M. (2008). Profit and Profit Theory. In S. N. Durlauf, and L. E. Blume (Eds.), The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics Online, 1–11. Palgrave Macmillan, 2nd edition. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2011). The Emergence of Profit and Interest in the Monetary Circuit. SSRN Working Paper Series, 1973952: 1–23. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2013). Debunking Squared. SSRN Working Paper Series, 2357902: 1–5. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2014a). The Profit Theory is False Since Adam Smith. What About the True Distribution Theory? SSRN Working Paper Series, 2511741: 1–23. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2014b). The Synthesis of Economic Law, Evolution, and History. SSRN Working Paper Series, 2500696: 1–22. URL

Keen, S. (2010). Solving the Paradox of Monetary Profits. Economics E-Journal, 4(2010-31). URL

For more about the Profit Law see AXECquery.

***

Wikimedia AXEC143d

Deconfusing confused confusers

Comment on Peter Radford on 'Economic Realism'

Blog-Reference

With reference to the thread 'Mainstream macroeconomics distorts our understanding of economic reality' (here) you write “I don’t want to get dragged into what appears to be an endless, and pointless, debate … but.”

So you do not want to participate in the discussion but instead, do a bit of meta-communication. This is not exactly the way to steer a discussion to worthwhile conclusions.

In the style of a film critic, you sum up: endless and pointless. As a matter of fact, the discussion arrived at some clear-cut results. Everybody can convince himself that your resume is far from reality. These were the major results (here):

In more detail, there can be no longer any reasonable doubt about:

First of all, one has to distinguish between theoretical and political economics. The goal of political economics is to push an agenda, the goal of theoretical economics is to explain how the actual economy works. From the viewpoint of science political economics as a whole is a no-go. The first problem of economics is that many economists are not scientists but agenda pushers of one sort or another.

Political economics is, as everybody knows, scientifically worthless.

You write: “But, of course, humans are inherently political. We were political before we were economical.”

This is true, of course. But this is the subject matter of Politics/Psychology/Sociology / Anthropology ― NOT of economics. The task of economists is to explain how the actual economy works. Economics is not a science of behavior. No way leads from any assumption about human behavior to the understanding of the economic system.

There is only one way to get out of the scientific slums of political economics and that is: to move from subjective to objective axiomatic foundations.

While political economics is indeed thriving on endless confusion, theoretical economics has an answer that is unsurpassable in its definitive clarity

That is down-to-earth scientific realism.

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

Blog-Reference

With reference to the thread 'Mainstream macroeconomics distorts our understanding of economic reality' (here) you write “I don’t want to get dragged into what appears to be an endless, and pointless, debate … but.”

So you do not want to participate in the discussion but instead, do a bit of meta-communication. This is not exactly the way to steer a discussion to worthwhile conclusions.

In the style of a film critic, you sum up: endless and pointless. As a matter of fact, the discussion arrived at some clear-cut results. Everybody can convince himself that your resume is far from reality. These were the major results (here):

- Orthodoxy is a failure.

- Heterodoxy is a failure.

In more detail, there can be no longer any reasonable doubt about:

- Neither orthodox nor heterodox economists have a clear idea of the fundamental concepts income and profit.

- The profit theory is false since Adam Smith.

- Because economists fail to capture the essence of the market system they have no valid theory about how the economy works.

- Keynes' fundamental equations of macroeconomics, i.e. Income = value of output = consumption + investment. Saving = income – consumption. Therefore saving = investment, are indefensible. That is why Keynesianism is a failure.

- At present, economics is not built upon a set of acceptable premises or axioms.

- Heterodoxy does not meet the formal minimum standards of theoretical economics.

- Psychology / Sociology / Philosophy is outside of science.

- Orthodoxy is built upon unacceptable behavioral axioms, therefore, a paradigm shift is inevitable.

- The definition ‘Economics is the science which studies human behavior as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses’ has misled research in the direction of pseudo-sociology and pseudo-psychology.

- Economics is the science that studies how the economic system works.

First of all, one has to distinguish between theoretical and political economics. The goal of political economics is to push an agenda, the goal of theoretical economics is to explain how the actual economy works. From the viewpoint of science political economics as a whole is a no-go. The first problem of economics is that many economists are not scientists but agenda pushers of one sort or another.

Political economics is, as everybody knows, scientifically worthless.

You write: “But, of course, humans are inherently political. We were political before we were economical.”

This is true, of course. But this is the subject matter of Politics/Psychology/Sociology / Anthropology ― NOT of economics. The task of economists is to explain how the actual economy works. Economics is not a science of behavior. No way leads from any assumption about human behavior to the understanding of the economic system.

There is only one way to get out of the scientific slums of political economics and that is: to move from subjective to objective axiomatic foundations.

While political economics is indeed thriving on endless confusion, theoretical economics has an answer that is unsurpassable in its definitive clarity

► there is no alternative to the Structural Axiomatic Paradigm◄

That is down-to-earth scientific realism.

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

Still alive in some heads: equilibrium

Comment on Lars Syll on 'Still dead after all these years — general equilibrium theory'

Blog-Reference

You describe the equilibrium metaphor. This is storytelling. The question is whether this metaphor is applicable to the economy. And the definitive answer is: IT IS NOT: “The mathematical failure of general equilibrium is such a shock to established theory that it is hard for many economists to absorb its full impact.” (Ackerman, 2004, p. 19)

Some people, however, simply cannot get their heads around it: “And so — faithful to the theory's conceptual cornerstones and hoping against all hope that the unthinkable may still be achieved (i.e., a satisfactory theory of the price mechanism) — the tormented upholders of the validity of the paradigmatic core of economic equilibrium theory appear singularly reluctant to face the problem of comparing expectations and results and assessing the consistency of the theory.” (Ingrao et al, 1990, p. 346)

You seem to be one of those people. Just in case you are really interested in the correct theory of the price mechanism see (2014).

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Ackerman, F. (2004). Still Dead After All These Years: Interpreting the Failure of General Equilibrium Theory. In F. Ackerman, and A. Nadal (Eds.), The Flawed Foundations of General Equilibrium, 14–32. London, New York: Routledge.

Ingrao, B., and Israel, G. (1990). The Invisible Hand. Economic Equilibrium in the History of Science. Cambridge, London: MIT Press.

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2014). Economics for Economists. SSRN Working Paper Series, 2517242: 1–29. URL

Blog-Reference

You describe the equilibrium metaphor. This is storytelling. The question is whether this metaphor is applicable to the economy. And the definitive answer is: IT IS NOT: “The mathematical failure of general equilibrium is such a shock to established theory that it is hard for many economists to absorb its full impact.” (Ackerman, 2004, p. 19)

Some people, however, simply cannot get their heads around it: “And so — faithful to the theory's conceptual cornerstones and hoping against all hope that the unthinkable may still be achieved (i.e., a satisfactory theory of the price mechanism) — the tormented upholders of the validity of the paradigmatic core of economic equilibrium theory appear singularly reluctant to face the problem of comparing expectations and results and assessing the consistency of the theory.” (Ingrao et al, 1990, p. 346)

You seem to be one of those people. Just in case you are really interested in the correct theory of the price mechanism see (2014).

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Ackerman, F. (2004). Still Dead After All These Years: Interpreting the Failure of General Equilibrium Theory. In F. Ackerman, and A. Nadal (Eds.), The Flawed Foundations of General Equilibrium, 14–32. London, New York: Routledge.

Ingrao, B., and Israel, G. (1990). The Invisible Hand. Economic Equilibrium in the History of Science. Cambridge, London: MIT Press.

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2014). Economics for Economists. SSRN Working Paper Series, 2517242: 1–29. URL

First Fundamental Law vs Fundamental Theorem of Income Distribution

Comment on RWER issue 69 on Piketty's Capital

Blog-Reference

“In the early pages of Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty states a 'fundamental law of capitalism' that α = rxβ, where α is the share of profit in income, β is the capital/output ratio, and r is the rate of return on capital, or the rate of profit. Thus: r = α/β.” (Galbraith, 2014, p. 145)

The fundamental law does not hold because the fundamental theorem of income distribution states: Profit is not a factor income (2012, p. 4).

Piketty does not realize that profit and distributed profit are fundamentally different economic entities. Therefore, there is no such thing as “a share of profit in income” but there is “a share of distributed profit in income”.

The axiomatically correct macroeconomic Profit Law reads

(i) for the elementary production-consumption economy with profit distribution

Qm≡Yd−Sm (2012, p. 4, eq. (5)),

(ii) for the investment economy with profit distribution,

Qm ≡Yd+I−Sm: (2014, p. 8, eq. (18)).

Legend: Qm monetary profit, Yd distributed profit, Sm monetary saving, I investment expenditure

The structural axiomatic Profit Law gets a bit more sophisticated when foreign trade and government is included. Summing up investment expenditures over time and taking depreciation into account (ii) ultimately yields the profit rate (2011b, Sec. 6.2).

Note that profit for the economy as a whole does not depend on productivity. What holds for a single firm does not hold for the economy as a whole. One has to be careful here not to commit the Fallacy of Composition.

Changes in the valuation price of assets are captured by nonmonetary profit Qn. This is a different and lengthy issue (2011a).

From the fact that Piketty's profit theory is not correct follows logically that his First Fundamental Law is not correct either.

Time to get the formal foundations right (see here).

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Galbraith, J. K. (2014). Unpacking the First Fundamental Law. real-world economics review, (69): 145–148. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2011a). Primary and Secondary Markets. SSRN Working Paper Series, 1917012: 1–26. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2011b). Squaring the Investment Cycle. SSRN Working Paper Series, 1911796: 1–25. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2012). Income Distribution, Profit, and Real Shares. SSRN Working Paper Series, 2012793: 1–13. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2014). The Three Fatal Mistakes of Yesterday Economics: Profit, I=S, Employment. SSRN Working Paper Series, 2489792: 1–13. URL

The 'First Fundamental Law of Capitalism' is the Profit Law (see Wikimedia AXEC143d). For details of the big picture see cross-references Profit.

Blog-Reference

“In the early pages of Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty states a 'fundamental law of capitalism' that α = rxβ, where α is the share of profit in income, β is the capital/output ratio, and r is the rate of return on capital, or the rate of profit. Thus: r = α/β.” (Galbraith, 2014, p. 145)

The fundamental law does not hold because the fundamental theorem of income distribution states: Profit is not a factor income (2012, p. 4).

Piketty does not realize that profit and distributed profit are fundamentally different economic entities. Therefore, there is no such thing as “a share of profit in income” but there is “a share of distributed profit in income”.

The axiomatically correct macroeconomic Profit Law reads

(i) for the elementary production-consumption economy with profit distribution

Qm≡Yd−Sm (2012, p. 4, eq. (5)),

(ii) for the investment economy with profit distribution,

Qm ≡Yd+I−Sm: (2014, p. 8, eq. (18)).

Legend: Qm monetary profit, Yd distributed profit, Sm monetary saving, I investment expenditure

The structural axiomatic Profit Law gets a bit more sophisticated when foreign trade and government is included. Summing up investment expenditures over time and taking depreciation into account (ii) ultimately yields the profit rate (2011b, Sec. 6.2).

Note that profit for the economy as a whole does not depend on productivity. What holds for a single firm does not hold for the economy as a whole. One has to be careful here not to commit the Fallacy of Composition.

Changes in the valuation price of assets are captured by nonmonetary profit Qn. This is a different and lengthy issue (2011a).

From the fact that Piketty's profit theory is not correct follows logically that his First Fundamental Law is not correct either.

Time to get the formal foundations right (see here).

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Galbraith, J. K. (2014). Unpacking the First Fundamental Law. real-world economics review, (69): 145–148. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2011a). Primary and Secondary Markets. SSRN Working Paper Series, 1917012: 1–26. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2011b). Squaring the Investment Cycle. SSRN Working Paper Series, 1911796: 1–25. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2012). Income Distribution, Profit, and Real Shares. SSRN Working Paper Series, 2012793: 1–13. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2014). The Three Fatal Mistakes of Yesterday Economics: Profit, I=S, Employment. SSRN Working Paper Series, 2489792: 1–13. URL

The 'First Fundamental Law of Capitalism' is the Profit Law (see Wikimedia AXEC143d). For details of the big picture see cross-references Profit.

The profit theory is false since Adam Smith. What can you expect from distribution theory?

Comment on RWER issue 69 on Piketty's Capital

Blog-Reference

Critical economists never bought into marginalism as a theory of income distribution (Syll, 2014, p. 40) and it is clear by now that the orthodox approach is a failure. Quite naturally, Heterodoxy is drawn to Marx. Unfortunately, Marx also got it wrong. For the formal proof see (2014).

All major economic schools lack a consistent profit theory and therefore all distribution theories are hanging in the air. Piketty is no exception.

As Hicks already observed with regard to profit: economics is “a science still groping in the dark” (1931, p. 170). Economists have no true conception of the most important phenomenon in their universe. What is immediately obvious is that the theories of income distribution and wealth distribution are wrong by logical necessity.

The first step out of the cul-de-sac is (2012)

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Hicks, J. R. (1931). The Theory of Uncertainty and Profit. Economica, (32):

170–189. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2012). Income Distribution, Profit, and Real Shares. SSRN

Working Paper Series, 2012793: 1–13. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2014). Profit for Marxists. SSRN Working Paper Series,

2414301: 1–25. URL

Syll, L. P. (2014). Piketty and the Limits of Marginal Productivity Theory. realworld

economics review, (69): 36–43. URL

For an overview about the desolate state of profit theory, which has been known for

a long time but never rectified, see the web page here

Blog-Reference

Critical economists never bought into marginalism as a theory of income distribution (Syll, 2014, p. 40) and it is clear by now that the orthodox approach is a failure. Quite naturally, Heterodoxy is drawn to Marx. Unfortunately, Marx also got it wrong. For the formal proof see (2014).

All major economic schools lack a consistent profit theory and therefore all distribution theories are hanging in the air. Piketty is no exception.

As Hicks already observed with regard to profit: economics is “a science still groping in the dark” (1931, p. 170). Economists have no true conception of the most important phenomenon in their universe. What is immediately obvious is that the theories of income distribution and wealth distribution are wrong by logical necessity.

The first step out of the cul-de-sac is (2012)

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Hicks, J. R. (1931). The Theory of Uncertainty and Profit. Economica, (32):

170–189. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2012). Income Distribution, Profit, and Real Shares. SSRN

Working Paper Series, 2012793: 1–13. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2014). Profit for Marxists. SSRN Working Paper Series,

2414301: 1–25. URL

Syll, L. P. (2014). Piketty and the Limits of Marginal Productivity Theory. realworld

economics review, (69): 36–43. URL

For an overview about the desolate state of profit theory, which has been known for

a long time but never rectified, see the web page here

From behavior to structure

Comment on Asad Zaman on 'Why does aggregate demand collapse?'

Blog-Reference

Blog-Reference

It is important to distinguish between political and theoretical economics. In political economics 'anything goes'; in theoretical economics, scientific standards are observed.

The crucial point is: political economics is based on behavioral axioms (McKenzie, 2008) and this is not a solid enough foundation: “. . . if we wish to place economic science upon a solid basis, we must make it completely independent of psychological assumptions and philosophical hypotheses.” (Slutzky, quoted in Mirowski, 1995, p. 362)

To start with behavioral assumptions like the profit motive invariably leads to a gossip model of the world. This is not to say that the profit motive is 'unrealistic'. What is said is that second-guessing the agents is a pointless exercise: “... there has been no progress in developing laws of human behavior for the last twenty-five hundred years.” (Hausman, 1992, p. 320), (Rosenberg, 1980, pp. 2-3)

Many economists tend to think that they are doing science while they never get above the level of gossiping about what the agents want or think or expect.

The upshot is that no way leads from the understanding of how agents behave to the understanding of how the economic system behaves (2014).

This fully explains the failure of behavior-based approaches ― including, of course, the Austrians.

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Hausman, D. M. (1992). The Inexact and Separate Science of Economics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2014). Objective Principles of Economics. SSRN Working Paper Series, 2418851: 1–19. URL

McKenzie, L. W. (2008). General Equilibrium. In S. N. Durlauf, and L. E. Blume (Eds.), The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics Online, 1–18. Palgrave

Macmillan, 2nd edition. URL

Mirowski, P. (1995). More Heat than Light. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Rosenberg, A. (1980). Sociobiology and the Preemption of Social Science. Oxford: Blackwell.

Listen to the EconoPhysicists

Comment on Lars Syll on ‘Modern macroeconomics and the perils of using 'Mickey-Mouse' models’

Blog-Reference

When Econophysicists take a look at theoretical economics from their distinct point of view the conclusions are always interesting. Take this one about the future of conventional economics.

“What is now taught as standard economic theory will eventually disappear, no trace of it will remain in the universities or boardrooms because it simply doesn’t work: were it engineering, the bridge would collapse.” (McCauley, 2006, p. 17)

Or this one about the art of model-building.

“There is little or nothing in existing micro- or macroeconomics texts that is of value for understanding real markets. Economists have not understood how to model markets mathematically in an empirically correct way.” (McCauley, 2006, p. 16)

I think Heterodoxy can agree with all this. My main point with the econophysicists is this: conventional economics is largely the product of old-school econophysicists (see also 2013). There is a lot of ironies here.

Beginning with the Classicals economists have shaped economics in the image of physics. Mirowski has brilliantly retold the story (1995).

While it is legitimate to copy from physics one has to make sure that one gets the crucial point. In most cases, the copying remained on the surface.

“Now there is simply no doubt that whatever was the source of inspiration for Jevons, Menger and Walras, all three invoked whatever physics they knew to lend prestige to their theoretical innovations. Unfortunately, with the exception of Jevons, that was the physics of Newton, not the physics of Helmholz, Joule and Maxwell; Adam Smith, Ricardo, James Mill and McCulloch had been just as eager in earlier days to invoke the name of Newton to legitimise their theoretical claims.” (Blaug, 1989, p. 1226)

On the whole, the copying amounts regularly to take the powerful tools that have been invented elsewhere (Darwinism is also popular) and to apply them to economics. It is a bit like Schwarzenegger grabbing the cruise missile and then going to wipe out the rather unpleasant guy next door.

In my mind, the best lesson physics has to offer is that you have to think for yourself and to create your own tools.

“The mathematical language used to formulate a theory is usually taken for granted. However, it should be recognized that most of mathematics used in physics was developed to meet the theoretical needs of physics. ... The moral is that the symbolic calculus employed by a scientific theory should be tailored to the theory, not the other way round.” (Wittgenstein, quoted in Schmiechen, 2009, p. 368)

The take-home message is Theory first!

So I have some qualms about whether the Affine Robust Measurement Feedback Non-linear H-infinity Control is the appropriate tool in economics. In any case, it sounds good. But is this real progress compared to the old-school econophysicists who messed the whole thing up in the first place?

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Blaug, M. (1989). Review. Economic Journal, 99(398): 1225–1226. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2013). Toolism! A Critique of Econophysics. SSRN Working

Paper Series, 2257841: 1–13. URL

McCauley, J. L. (2006). Response to "Worrying Trends in Econophysics". Econo-

Physics Forum, 0601001: 1–26. URL

Mirowski, P. (1995). More Heat than Light. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schmiechen, M. (2009). Newton’s Principia and Related ‘Principles’ Revisited,

volume 1. Norderstedt: Books on Demand BoD, 2nd edition. URL

Blog-Reference

When Econophysicists take a look at theoretical economics from their distinct point of view the conclusions are always interesting. Take this one about the future of conventional economics.

“What is now taught as standard economic theory will eventually disappear, no trace of it will remain in the universities or boardrooms because it simply doesn’t work: were it engineering, the bridge would collapse.” (McCauley, 2006, p. 17)

Or this one about the art of model-building.

“There is little or nothing in existing micro- or macroeconomics texts that is of value for understanding real markets. Economists have not understood how to model markets mathematically in an empirically correct way.” (McCauley, 2006, p. 16)

I think Heterodoxy can agree with all this. My main point with the econophysicists is this: conventional economics is largely the product of old-school econophysicists (see also 2013). There is a lot of ironies here.

Beginning with the Classicals economists have shaped economics in the image of physics. Mirowski has brilliantly retold the story (1995).

While it is legitimate to copy from physics one has to make sure that one gets the crucial point. In most cases, the copying remained on the surface.

“Now there is simply no doubt that whatever was the source of inspiration for Jevons, Menger and Walras, all three invoked whatever physics they knew to lend prestige to their theoretical innovations. Unfortunately, with the exception of Jevons, that was the physics of Newton, not the physics of Helmholz, Joule and Maxwell; Adam Smith, Ricardo, James Mill and McCulloch had been just as eager in earlier days to invoke the name of Newton to legitimise their theoretical claims.” (Blaug, 1989, p. 1226)

On the whole, the copying amounts regularly to take the powerful tools that have been invented elsewhere (Darwinism is also popular) and to apply them to economics. It is a bit like Schwarzenegger grabbing the cruise missile and then going to wipe out the rather unpleasant guy next door.

In my mind, the best lesson physics has to offer is that you have to think for yourself and to create your own tools.

“The mathematical language used to formulate a theory is usually taken for granted. However, it should be recognized that most of mathematics used in physics was developed to meet the theoretical needs of physics. ... The moral is that the symbolic calculus employed by a scientific theory should be tailored to the theory, not the other way round.” (Wittgenstein, quoted in Schmiechen, 2009, p. 368)

The take-home message is Theory first!

So I have some qualms about whether the Affine Robust Measurement Feedback Non-linear H-infinity Control is the appropriate tool in economics. In any case, it sounds good. But is this real progress compared to the old-school econophysicists who messed the whole thing up in the first place?

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Blaug, M. (1989). Review. Economic Journal, 99(398): 1225–1226. URL

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2013). Toolism! A Critique of Econophysics. SSRN Working

Paper Series, 2257841: 1–13. URL

McCauley, J. L. (2006). Response to "Worrying Trends in Econophysics". Econo-

Physics Forum, 0601001: 1–26. URL

Mirowski, P. (1995). More Heat than Light. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schmiechen, M. (2009). Newton’s Principia and Related ‘Principles’ Revisited,

volume 1. Norderstedt: Books on Demand BoD, 2nd edition. URL

Shocking: methodology is a tricky business

Comment on Peter Radford on 'Study the shocks'

Blog-Reference

What is the core problem of economics? Bagehot made it clear back in 1885: “It [Political Economy] is an abstract science which labours under a special hardship. Those who are conversant with its abstractions are usually without a true contact with its facts; those who are in contact with its facts have usually little sympathy with and little cognisance of its abstractions. Literary men who write about it are constantly using what a great teacher calls 'unreal words,' ― that is, they are using expressions with which they have no complete vivid picture to correspond. They are like physiologists who have never dissected; like astronomers who have never seen the stars; and, in consequence, just when they seem to be reasoning at their best, their knowledge of the facts falls short. Their primitive picture fails them, and their deduction altogether misses the mark ― sometimes, indeed, goes astray so far, that those who live and move among the facts boldly say that they cannot comprehend 'how any one can talk such nonsense.' Yet, on the other hand, these people who live and move among the facts often, or mostly, cannot of themselves put together any precise reasonings about them.” (1885, PE.13)

Take-home message: There are two types of economists but neither has a clue.

This, indeed, was not news then because J. S. Mill reported already in 1874 about the two classes of inquirers: “It has been again and again demonstrated, that those who are accused of despising facts and disregarding experience build and profess to build wholly upon facts and experience; while those who disavow theory cannot make one step without theorizing. But, although both classes of inquirers do nothing but theorize, and both of them consult no other guide than experience, there is this difference between them, and a most important difference it is: that those who are called practical men require specific experience, and argue wholly upwards from particular facts to a general conclusion; while those who are called theorists aim at embracing a wider field of experience, and, having argued upwards from particular facts to a general principle including a much wider range than that of the question under discussion, then argue downwards from that general principle to a variety of specific conclusions.” (Mill, 1874, V. 43)

Take-home message: There are two types of economists, the upwarders and downwarders, but neither is particularly successful.

Mill was confronted with a quite unsatisfactory situation. He was well aware of the “backward state” of the social sciences in general and of economics in particular. Being one of the finest methodologists of his time he took sides: “Since, therefore, it is vain to hope that truth can be arrived at, either in Political Economy or in any other department of the social science, while we look at the facts in the concrete, clothed in all the complexity with which nature has surrounded them, and endeavour to elicit a general law by a process of induction from a comparison of details; there remains no other method than the à priori one, or that of "abstract speculation".” (Mill, 1874, V.55)

Mill had the great triumph of the downwarders before his eyes and he certainly concurred with Galileo: “I shall never be able to express strongly enough my admiration for the greatness of mind of these men who conceived this [heliocentric] hypothesis and held it to be true. In violent opposition to the evidence of their own senses and by sheer force of intellect, they preferred what reason told them to that which sense experience plainly showed them ...” (quoted in Popper, 1994, p. 84)

In contrast, the defeat of the upwarders was evident and their good advice rang hollow: “Bacon, the philosopher of science, was, quite consistently, an enemy of the Copernican hypothesis. Don't theorize, he said, but open your eyes and observe without prejudice, and you cannot doubt that the Sun moves and that the Earth is at rest.” (Popper, 1994, p. 84)

Take-home message: Common sense and open eyes can be very misleading in scientific matters.

Or, as Marx put it: “That in their appearances things are often presented in an inverted way is something fairly familiar in every science, apart from political economy.” (Marx, 1990, p. 677)

Mill knew quite well that methodology can point out errors, mistakes, nonentities, fallacies, and green cheese assumptionism but that it is beyond the means of the methodologist to tell researchers how to solve their scientific problems. And if any methodologist should ever think he knows how to do better there is a straightforward way to demonstrate it: “Doubtless, the most effectual mode of showing how the sciences of Ethics and Politics may be constructed, would be to construct them ...” (Mill, 2006, p. 834)

The downwarders of Orthodoxy have failed to explain how the actual economy works. This, however, does not prove that the methodology of the upwarders is superior. Heterodoxy cannot claim that it has performed better.

My good advice to Peter Radford could be: Never give good advice in methodological matters, but this would be much like one of these logically shocking ancient Greek paradoxes.

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Bagehot, W. (1885). The Postulates of English Political Economy. Library of Economics and Liberty. URL

Marx, K. (1990). Capital, Volume I. London: Penguin Classics.

Mill, J. S. (1874). Essays on Some Unsettled Questions of Political Economy. On the Definition of Political Economy; and on the Method of Investigation Proper To It. Library of Economics and Liberty. URL

Mill, J. S. (2006). A System of Logic Ratiocinative and Inductive. Being a Connected View of the Principles of Evidence and the Methods of Scientific Investigation, Vol. 8 of Collected Works of John Stuart Mill. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

Popper, K. R. (1994). The Myth of the Framework. In Defence of Science and Rationality., chapter Science: Problems, Aims, Responsibilities, 82–111. London, New York: Routledge.

Blog-Reference

What is the core problem of economics? Bagehot made it clear back in 1885: “It [Political Economy] is an abstract science which labours under a special hardship. Those who are conversant with its abstractions are usually without a true contact with its facts; those who are in contact with its facts have usually little sympathy with and little cognisance of its abstractions. Literary men who write about it are constantly using what a great teacher calls 'unreal words,' ― that is, they are using expressions with which they have no complete vivid picture to correspond. They are like physiologists who have never dissected; like astronomers who have never seen the stars; and, in consequence, just when they seem to be reasoning at their best, their knowledge of the facts falls short. Their primitive picture fails them, and their deduction altogether misses the mark ― sometimes, indeed, goes astray so far, that those who live and move among the facts boldly say that they cannot comprehend 'how any one can talk such nonsense.' Yet, on the other hand, these people who live and move among the facts often, or mostly, cannot of themselves put together any precise reasonings about them.” (1885, PE.13)

Take-home message: There are two types of economists but neither has a clue.

This, indeed, was not news then because J. S. Mill reported already in 1874 about the two classes of inquirers: “It has been again and again demonstrated, that those who are accused of despising facts and disregarding experience build and profess to build wholly upon facts and experience; while those who disavow theory cannot make one step without theorizing. But, although both classes of inquirers do nothing but theorize, and both of them consult no other guide than experience, there is this difference between them, and a most important difference it is: that those who are called practical men require specific experience, and argue wholly upwards from particular facts to a general conclusion; while those who are called theorists aim at embracing a wider field of experience, and, having argued upwards from particular facts to a general principle including a much wider range than that of the question under discussion, then argue downwards from that general principle to a variety of specific conclusions.” (Mill, 1874, V. 43)

Take-home message: There are two types of economists, the upwarders and downwarders, but neither is particularly successful.

Mill was confronted with a quite unsatisfactory situation. He was well aware of the “backward state” of the social sciences in general and of economics in particular. Being one of the finest methodologists of his time he took sides: “Since, therefore, it is vain to hope that truth can be arrived at, either in Political Economy or in any other department of the social science, while we look at the facts in the concrete, clothed in all the complexity with which nature has surrounded them, and endeavour to elicit a general law by a process of induction from a comparison of details; there remains no other method than the à priori one, or that of "abstract speculation".” (Mill, 1874, V.55)

Mill had the great triumph of the downwarders before his eyes and he certainly concurred with Galileo: “I shall never be able to express strongly enough my admiration for the greatness of mind of these men who conceived this [heliocentric] hypothesis and held it to be true. In violent opposition to the evidence of their own senses and by sheer force of intellect, they preferred what reason told them to that which sense experience plainly showed them ...” (quoted in Popper, 1994, p. 84)

In contrast, the defeat of the upwarders was evident and their good advice rang hollow: “Bacon, the philosopher of science, was, quite consistently, an enemy of the Copernican hypothesis. Don't theorize, he said, but open your eyes and observe without prejudice, and you cannot doubt that the Sun moves and that the Earth is at rest.” (Popper, 1994, p. 84)

Take-home message: Common sense and open eyes can be very misleading in scientific matters.

Or, as Marx put it: “That in their appearances things are often presented in an inverted way is something fairly familiar in every science, apart from political economy.” (Marx, 1990, p. 677)

Mill knew quite well that methodology can point out errors, mistakes, nonentities, fallacies, and green cheese assumptionism but that it is beyond the means of the methodologist to tell researchers how to solve their scientific problems. And if any methodologist should ever think he knows how to do better there is a straightforward way to demonstrate it: “Doubtless, the most effectual mode of showing how the sciences of Ethics and Politics may be constructed, would be to construct them ...” (Mill, 2006, p. 834)

The downwarders of Orthodoxy have failed to explain how the actual economy works. This, however, does not prove that the methodology of the upwarders is superior. Heterodoxy cannot claim that it has performed better.

My good advice to Peter Radford could be: Never give good advice in methodological matters, but this would be much like one of these logically shocking ancient Greek paradoxes.

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Bagehot, W. (1885). The Postulates of English Political Economy. Library of Economics and Liberty. URL

Marx, K. (1990). Capital, Volume I. London: Penguin Classics.

Mill, J. S. (1874). Essays on Some Unsettled Questions of Political Economy. On the Definition of Political Economy; and on the Method of Investigation Proper To It. Library of Economics and Liberty. URL

Mill, J. S. (2006). A System of Logic Ratiocinative and Inductive. Being a Connected View of the Principles of Evidence and the Methods of Scientific Investigation, Vol. 8 of Collected Works of John Stuart Mill. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

Popper, K. R. (1994). The Myth of the Framework. In Defence of Science and Rationality., chapter Science: Problems, Aims, Responsibilities, 82–111. London, New York: Routledge.

Between the devil and the deep blue sea: on framing false alternatives

Comment on Merijn Knibbe on 'The DSGE emperor has no clothes. But he does have a hat. And a rabbit.'

Blog-Reference

Imagine for a moment that you drop into a discussion. Two experts talk about the respective merits and demerits of the A-car and the B-car. There is a lot of technical argument about acceleration, fuel consumption, operating distance, cylinder capacity, electronic injection, etcetera. Both debaters are engaged and obviously conversant with the technicalities. In the end, the A-car proponent seems to have the better arguments. Good discussion, applause. Then you learn that the original question was: How can we get to the moon?

Much of the discussion about DSGE and WUMM is of this sort. The question was: After the recent spectacular failure of macroeconomics, how can we do better in the future? How to proceed theoretically and analytically and empirically? Is DSGE or WUMM more promising? This is false framing. The correct answer is, neither DSGE nor WUMM, both have to be abandoned.

Why? Because there is something like falsification.

“In economics we should strive to proceed, wherever we can, exactly according to the standards of the other, more advanced, sciences, where it is not possible, once an issue has been decided, to continue to write about it as if nothing had happened.” (Morgenstern, 1941, pp. 369-370)

Of course, after a severe crisis, economists do not simply continue, they promise to do better in the future. Yes, and they have already an idea. More complexity, for example. Mea culpa, we failed in the past, but this time we fix it.

Not much will come from this cosmetic surgery. Why?

To make a long argument short please accept for a moment the assertion: There is no such thing as a law of human behavior. From this follows trivially

All these difficulties that make model testing such a challenging task have their root in the foundational assumption that there is such a thing as a behavioral law or at least a regularity. After all, that is what we are ultimately looking for. Because if there is no law nobody can make a prediction (except charlatans and doomsayers).

DSGE claims to be based on “deep structural parameters.” This would be fine if it indeed were the case. Yet the whole microfoundations project is essentially about optimizing behavior. This crucial assumption is put squarely into the premises

“Modern macro models have the five following properties:

Two of the five premises are about human behavior and most people are aware that they are far off the mark. This, however, is a minor problem. The Iron Law of Economic Theory Design says: No way leads from the understanding of human motivations and behavior or from purely speculative behavioral assumptions to the understanding of how the economy works (for details see 2014).

Hence, what is needed is not cosmetic surgery but a paradigm shift. The whole set of DSGE premises, which is in the main shared by WUMM, is methodologically mistaken and ultimately indefensible.

Therefore, the choice is not between DSGE or WUMM. The real choice is between the defunct subjective-behavioral approach and a new paradigm. This, though, is obvious since Keynes and the Great Depression. The real problem is not in statistical technicalities but in “... a failure of reason to find suitable alternatives which might be used to transcend an accidental intermediate stage of our knowledge.” (Feyerabend, 2004, p. 72)

There are many popular and even good reasons to blame Orthodoxy for the latest crisis, but ― to set the record straight ― Heterodoxy, too, did not come up with a “suitable alternative” since Keynes proposed to “throw over” the classical axioms (Keynes, 1973, p. 16).

Heterodoxy has a mission: Don't waste time with blaming and false alternatives; dig deeper; there are economic laws, but there are certainly no behavioral laws.

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Feyerabend, P. K. (2004). Problems of Empiricism. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2014). The Synthesis of Economic Law, Evolution, and

History. SSRN Working Paper Series, 2500696: 1–22. URL

Keynes, J. M. (1973). The General Theory of Employment Interest and Money.

The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes Vol. VII. London, Basingstoke:

Macmillan. (1936).

Morgenstern, O. (1941). Professor Hicks on Value and Capital. Journal of Political

Economy, 49(3): 361–393. URL

Blog-Reference

Imagine for a moment that you drop into a discussion. Two experts talk about the respective merits and demerits of the A-car and the B-car. There is a lot of technical argument about acceleration, fuel consumption, operating distance, cylinder capacity, electronic injection, etcetera. Both debaters are engaged and obviously conversant with the technicalities. In the end, the A-car proponent seems to have the better arguments. Good discussion, applause. Then you learn that the original question was: How can we get to the moon?

Much of the discussion about DSGE and WUMM is of this sort. The question was: After the recent spectacular failure of macroeconomics, how can we do better in the future? How to proceed theoretically and analytically and empirically? Is DSGE or WUMM more promising? This is false framing. The correct answer is, neither DSGE nor WUMM, both have to be abandoned.

Why? Because there is something like falsification.

“In economics we should strive to proceed, wherever we can, exactly according to the standards of the other, more advanced, sciences, where it is not possible, once an issue has been decided, to continue to write about it as if nothing had happened.” (Morgenstern, 1941, pp. 369-370)

Of course, after a severe crisis, economists do not simply continue, they promise to do better in the future. Yes, and they have already an idea. More complexity, for example. Mea culpa, we failed in the past, but this time we fix it.

Not much will come from this cosmetic surgery. Why?

To make a long argument short please accept for a moment the assertion: There is no such thing as a law of human behavior. From this follows trivially

- historical correlations are unreliable for forecasting purposes, particularly in the case of an entirely new situation, e.g. a regime change,

- demand and supply functions are nonentities,

- preferences change over time,

- parameters change over time,

- there is no equilibrium or steady state.

All these difficulties that make model testing such a challenging task have their root in the foundational assumption that there is such a thing as a behavioral law or at least a regularity. After all, that is what we are ultimately looking for. Because if there is no law nobody can make a prediction (except charlatans and doomsayers).

DSGE claims to be based on “deep structural parameters.” This would be fine if it indeed were the case. Yet the whole microfoundations project is essentially about optimizing behavior. This crucial assumption is put squarely into the premises

“Modern macro models have the five following properties:

- They specify budget constraints for households, technologies for firms, and resource constraints for the overall economy.

- They specify household preferences and firm objectives.

- They assume forward-looking behavior for firms and households.

- They include the shocks that firms and households face.

- They are models of the entire macroeconomy.”

Two of the five premises are about human behavior and most people are aware that they are far off the mark. This, however, is a minor problem. The Iron Law of Economic Theory Design says: No way leads from the understanding of human motivations and behavior or from purely speculative behavioral assumptions to the understanding of how the economy works (for details see 2014).

Hence, what is needed is not cosmetic surgery but a paradigm shift. The whole set of DSGE premises, which is in the main shared by WUMM, is methodologically mistaken and ultimately indefensible.

Therefore, the choice is not between DSGE or WUMM. The real choice is between the defunct subjective-behavioral approach and a new paradigm. This, though, is obvious since Keynes and the Great Depression. The real problem is not in statistical technicalities but in “... a failure of reason to find suitable alternatives which might be used to transcend an accidental intermediate stage of our knowledge.” (Feyerabend, 2004, p. 72)

There are many popular and even good reasons to blame Orthodoxy for the latest crisis, but ― to set the record straight ― Heterodoxy, too, did not come up with a “suitable alternative” since Keynes proposed to “throw over” the classical axioms (Keynes, 1973, p. 16).

Heterodoxy has a mission: Don't waste time with blaming and false alternatives; dig deeper; there are economic laws, but there are certainly no behavioral laws.

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Feyerabend, P. K. (2004). Problems of Empiricism. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2014). The Synthesis of Economic Law, Evolution, and

History. SSRN Working Paper Series, 2500696: 1–22. URL

Keynes, J. M. (1973). The General Theory of Employment Interest and Money.

The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes Vol. VII. London, Basingstoke:

Macmillan. (1936).

Morgenstern, O. (1941). Professor Hicks on Value and Capital. Journal of Political

Economy, 49(3): 361–393. URL

Yes, orthodox economics is poor science, but can Heterodoxy raise hope?

Comment on Lars Syll on 'Modern macroeconomics and the perils of using ‘Mickey Mouse’ models'

Blog-Reference

In 1898 the heterodox economist Thorstein Veblen asked: “Why is Economics Not an Evolutionary Science?”

What Veblen pointed out was that the petty mechanical models of his neoclassical fellow economists were mistaken, useless, and misleading.

He famously ridiculed homo oeconomicus: “The hedonistic conception of man is that of a lightning calculator of pleasures and pains who oscillates like a homogeneous globule of desire of happiness under the impulse of stimuli that shift him about the area, but leave him intact.”

Well said, indeed, and true to this day. Yet, one has to ask: Why did Veblen spend much time questioning and ridiculing Orthodoxy instead of developing evolutionary economics? If he knew what was wrong, why did he not demonstrate how to do it properly? Why is the very personification of Mickey Mouse economics ― homo oeconomicus ― still busy with maximizing utility in our days?

Yes, Orthodoxy is a failure. Yes, the heterodox critique is fully justified. Yes, the emperor has no clothes. Yes, the textbooks are wrong. Yes, linear models are unsatisfactory. Yes, equilibrium is a NONENTITY and rational expectations are a physical impossibility.

We have known all this since Veblen or even longer. Time enough, one would think, to develop something better.

Let all dreams come true and imagine for a moment that each orthodox economics professor is replaced by a heterodox professor. What could he teach? That there is something good and right with the Classics, with Marx, Walras, Keynes, the Austrians, Sraffa, Kalecki, and Minsky, but we do not know exactly what it is and how it fits together. Is the pluralism of partial or even falsified theories something that can be justified and taught as science?

The fact of the matter is that there is no heterodox alternative. To replace a paradigm means to replace obsolete axioms with new axioms. This effects a change of the whole theoretical superstructure and that is what a Paradigm Shift is all about. At the moment there exists no heterodox common ground in the form of a set of well-defined axioms and therefore nothing to consistently build upon.

Orthodoxy is unacceptable but its proponents have taken the pain to formulate its premises and conclusions in such a way that errors/mistakes can be identified with accepted scientific procedures. This is the minimum condition and this made it possible that General Equilibrium Theory could be refuted by its own proponents.

“The enemies, on the other hand, have proved curiously ineffective and they have very often aimed their arrows at the wrong targets. Indeed if it is the case that today General Equilibrium Theory is in some disarray, this is largely due to the work of General Equilibrium theorists, and not to any successful assault from outside.” (Hahn, 1980, p. 127)

Yes, nobody needs the Mickey Mouse models of Orthodoxy. But this is no sufficient reason to jump to heterodox Donald Duck models.

The common error lies in the assumption that there must be something like behavioral laws or at least regularities. There is no such thing. No way leads from behavioral assumptions to an understanding of how the actual economy works. The problem is not with the econometricians, the problem is with economic theory. From the assumption of utility maximization follows no testable relationship. It is the same with other green cheese assumptions like rational expectations, perfect competition, supply and demand functions, twice differentiable production functions, and all the rest (2013). Nonentities are not testable and that is not a weakness of statistical methods with a well-defined field of application. Standard economics simply falls outside this field.

As long as Heterodoxy, or anybody else for that matter, cannot replace the obsolete set of foundational assumptions with a consistent alternative, economics is caught in a cul-de-sac.

“Yet most economists neither seek alternative theories nor believe that they can be found.” (Hausman, 1992, p. 248)

Or, as Mirowski put it: “The task of producing knowledge against the grain requires imagination.” (2013, p. 4)

It is a scarce resource in economics.

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Hahn, F. H. (1980). General Equilibrium Theory. Public Interest. Special Issue: The Crisis in Economic Theory, 123–138.

Hausman, D. M. (1992). The Inexact and Separate Science of Economics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2013). Confused Confusers: How to Stop Thinking Like an Economist and Start Thinking Like a Scientist. SSRN Working Paper Series, 2207598: 1–16. URL

Mirowski, P. (2013). Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste. London, New York: Verso.

Related 'A social science is NOT a science but a sitcom' and 'The stupidity of Heterodoxy is the life insurance of Orthodoxy' and 'Homo oeconomicus: the never-ending folk-psychological shitshow'. For details of the big picture see cross-references NOT a Science of Behavior and cross-references Failed/Fake Scientists.

Blog-Reference

In 1898 the heterodox economist Thorstein Veblen asked: “Why is Economics Not an Evolutionary Science?”

What Veblen pointed out was that the petty mechanical models of his neoclassical fellow economists were mistaken, useless, and misleading.

He famously ridiculed homo oeconomicus: “The hedonistic conception of man is that of a lightning calculator of pleasures and pains who oscillates like a homogeneous globule of desire of happiness under the impulse of stimuli that shift him about the area, but leave him intact.”

Well said, indeed, and true to this day. Yet, one has to ask: Why did Veblen spend much time questioning and ridiculing Orthodoxy instead of developing evolutionary economics? If he knew what was wrong, why did he not demonstrate how to do it properly? Why is the very personification of Mickey Mouse economics ― homo oeconomicus ― still busy with maximizing utility in our days?

Yes, Orthodoxy is a failure. Yes, the heterodox critique is fully justified. Yes, the emperor has no clothes. Yes, the textbooks are wrong. Yes, linear models are unsatisfactory. Yes, equilibrium is a NONENTITY and rational expectations are a physical impossibility.

We have known all this since Veblen or even longer. Time enough, one would think, to develop something better.

Let all dreams come true and imagine for a moment that each orthodox economics professor is replaced by a heterodox professor. What could he teach? That there is something good and right with the Classics, with Marx, Walras, Keynes, the Austrians, Sraffa, Kalecki, and Minsky, but we do not know exactly what it is and how it fits together. Is the pluralism of partial or even falsified theories something that can be justified and taught as science?

The fact of the matter is that there is no heterodox alternative. To replace a paradigm means to replace obsolete axioms with new axioms. This effects a change of the whole theoretical superstructure and that is what a Paradigm Shift is all about. At the moment there exists no heterodox common ground in the form of a set of well-defined axioms and therefore nothing to consistently build upon.

Orthodoxy is unacceptable but its proponents have taken the pain to formulate its premises and conclusions in such a way that errors/mistakes can be identified with accepted scientific procedures. This is the minimum condition and this made it possible that General Equilibrium Theory could be refuted by its own proponents.

“The enemies, on the other hand, have proved curiously ineffective and they have very often aimed their arrows at the wrong targets. Indeed if it is the case that today General Equilibrium Theory is in some disarray, this is largely due to the work of General Equilibrium theorists, and not to any successful assault from outside.” (Hahn, 1980, p. 127)

Yes, nobody needs the Mickey Mouse models of Orthodoxy. But this is no sufficient reason to jump to heterodox Donald Duck models.

The common error lies in the assumption that there must be something like behavioral laws or at least regularities. There is no such thing. No way leads from behavioral assumptions to an understanding of how the actual economy works. The problem is not with the econometricians, the problem is with economic theory. From the assumption of utility maximization follows no testable relationship. It is the same with other green cheese assumptions like rational expectations, perfect competition, supply and demand functions, twice differentiable production functions, and all the rest (2013). Nonentities are not testable and that is not a weakness of statistical methods with a well-defined field of application. Standard economics simply falls outside this field.

As long as Heterodoxy, or anybody else for that matter, cannot replace the obsolete set of foundational assumptions with a consistent alternative, economics is caught in a cul-de-sac.

“Yet most economists neither seek alternative theories nor believe that they can be found.” (Hausman, 1992, p. 248)

Or, as Mirowski put it: “The task of producing knowledge against the grain requires imagination.” (2013, p. 4)

It is a scarce resource in economics.

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Hahn, F. H. (1980). General Equilibrium Theory. Public Interest. Special Issue: The Crisis in Economic Theory, 123–138.

Hausman, D. M. (1992). The Inexact and Separate Science of Economics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2013). Confused Confusers: How to Stop Thinking Like an Economist and Start Thinking Like a Scientist. SSRN Working Paper Series, 2207598: 1–16. URL

Mirowski, P. (2013). Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste. London, New York: Verso.

Related 'A social science is NOT a science but a sitcom' and 'The stupidity of Heterodoxy is the life insurance of Orthodoxy' and 'Homo oeconomicus: the never-ending folk-psychological shitshow'. For details of the big picture see cross-references NOT a Science of Behavior and cross-references Failed/Fake Scientists.

Throwing soap bubbles at time wasters

Comment on Lars Syll on 'Microfounded DSGE models ― a total waste of time!'

Blog-Reference

One defect is a bad thing, but countless defects are a good thing. This keeps the critics busy, the discussion lively, and the outcome forever inconclusive. Accordingly, Hahn was very happy with the critics of the neoclassical research program. “The enemies, on the other hand, have proved curiously ineffective and they have very often aimed their arrows at the wrong targets.” (Hahn, 1980, p. 127)

He even warned his colleagues of exuberance: “For as I said at the outset, the citadel is not at all secure and the fact that it is safe from a bombardment of soap bubbles does not mean that it is safe.” (Hahn, 1984, p. 78)

When homo oeconomicus was young and a simpleminded utility maximizer people laughed at him because of his unrealism. Poincaré, to be sure, choose his words: “Walras approached Poincaré for his approval. ... But Poincaré was devoutly committed to applied mathematics and did not fail to notice that utility is a nonmeasurable magnitude. ... He also wondered about the premises of Walras’s mathematics: It might be reasonable, as a first approximation, to regard men as completely self-interested, but the assumption of perfect foreknowledge 'perhaps requires a certain reserve'.” (Porter, 1994, p. 154)

What happened in the second approximation? Has nonsense been reduced since Walras? It has been multiplied by making it rigorous. This is what we actually have: 'an infinitely lived intertemporally optimizing representative household/consumer/producer, agents with homothetic and identical preferences, etc.' In the early days homo oeconomicus had only perfect foresight, now he has also eternal youth. Scientific progress is something different: “The last thirty years seem to this observer to have been downhill almost all the way. So much of the literature ... I see as silly beyond all expectation and unscholarly beyond all endurance.” (Leijonhufvud, 1998, p. 234)

Why have critics been so ineffective? Because they focus always on the most obvious weak link of the chain but do not understand the logic of the chain. J. S. Mill did, and he clearly stated the key question: “What are the propositions which may reasonably be received without proof? That there must be some such propositions all are agreed, since there cannot be an infinite series of proof, a chain suspended from nothing. But to determine what these propositions are, is the opus magnum of the more recondite mental philosophy.” (Mill, 2006, p. 746)

The fault of an approach lies always in the first element of the chain: in the axiomatic foundations. Keynes knew this: “For if orthodox economics is at fault, the error is to be found not in the superstructure, which has been erected with great care for logical consistency, but in a lack of clearness and of generality in the premises.” (Keynes, 1973, p. xxi)

An effective critique does not waste time with the plain unrealism of some heroic assumption in the middle of the chain. An effective critique finds a new hook to hang an impeccable logical chain on, that is, an effective critique changes the axiomatic foundations (2014; 2014).

After more than a century, it is pointless to repeat Poincaré's critique of homo oeconomicus. Homo emotionalis or homo sociologicus are not the solutions. Simply take ALL behavioral assumptions out of the formal foundations of economic theory. Second-guessing the agents is a waste of time: “... there has been no progress in developing laws of human behavior for the last twenty-five hundred years.” (Hausman, 1992, p. 320), (Rosenberg, 1980, pp. 2-3)

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Hahn, F. H. (1980). General Equilibrium Theory. Public Interest. Special Issue: The Crisis in Economic Theory, 123–138.

Hahn, F. H. (1984). Equilibrium and Macroeconomics. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hausman, D. M. (1992). The Inexact and Separate Science of Economics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.